The following project is associated with 60 Million Girls foundation - an organization that evaluates and funds various development projects aimed at educating girls. The foundation is based in Montreal, Canada and has funded projects in 14 countries around the world.

The foundation was born out of a dinner conversation where 8 women decided to take the initiative to do something about the incredible number of girls that were kept out of school because of various constraints. The success of the foundation is testament to the incredible power of initiative - how people can do what they want if they really put their heart and mind to it.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I had a brief interaction with these girls just before. They were quite amused to find visitors and particularly a photographer. Later, I caught them curiously waiting outside their classroom. Their stories are no doubt immensely interesting and I had certainly wished I had more to tell about them. All the same, they were battling it out against the odds to create a better life for themselves.

Our Journey starts at a coffee shop where Manuela and I first met. We had earlier exchanged e-mails where she invited me to consider an exciting project where she wanted to document the foundation`s work: seeing the real beneficiaries and tunneling through all the statistics. She wanted to know these girls and their stories first hand and my job was to somehow bring those stories to life through photography.

Manuela had dedicated herself to 60 million girls – a foundation that was born out of a dinner conversation among eight women and was testament to the power of initiative and dedication. It was not long after that I realized that the entire journey was about resilience and people doing their best to create a better world for others – be it the 8 founding members or the people we met at the camps. It was a story of selflessness and some how I was fortunate to be part of this tale.

My words cannot possibly express the strength and character of the people we met. They represent a mixture of tragedy, hope, witness, and perseverance. I came to admire them and appreciate their outlook and humility in the world.

This is a story about my journey and the details of what I saw and felt throughout. I can easily state that though my interactions were brief, they were sufficient to ignite a curiosity and a thought process that continues to this day and certainly will do so onwards. If there was anything that I hoped from this project from a personal standpoint - it was that I was inspired to find the same degree of selflessness and consider my works to somehow be in the benefit of others. Though this journey is quite a challenge and rests deeply on several unknowns, simply experiencing it is in itself an opportunity to learn and grow.

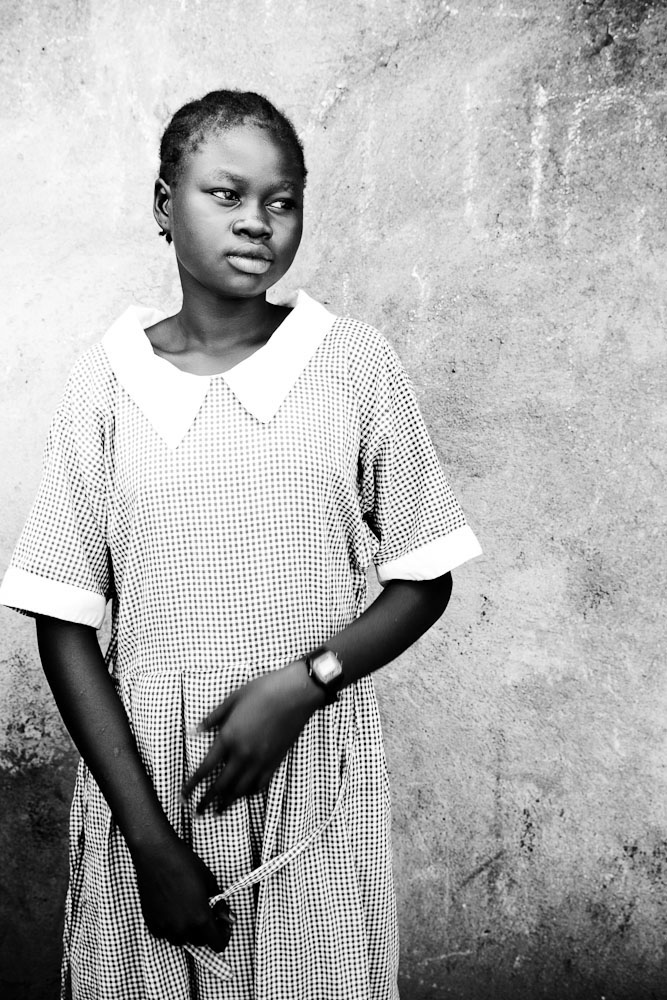

Margaret Achieng is 14 and in grade 6. She is one of the younger girls in the Girl Child Education program and there was something about her posture that I found very inspiring. She was a little shy but portrayed a degree of strength that was quite comforting. She says she has 6 siblings out which 5 are girls.

Some Background on the challenges of Refugees

To many of us, the sight of refugees are confined to television and reports as well as statistics. Like the global media, we tend to develop a sense of fatigue or even become desensitized to the situation and plight of refugees.

Indeed, the politics of refugees is quite complex. A 1951 convention on the protection of asylum seekers defines both the rights of refugees as well as the obligations of governments to offer protection. The convention and subsequent protocol limits the obligations of governments to cooperation with UNHCR, exemption from reciprocity, and information on national legislation concerning the rights and protection of refugees. While this is a crucial first step in offering protection to vulnerable refugees, it stops short of requiring nations to provide them with the freedom of development. They are restricted in the ease with which they can travel outside of the camps, seek employment or even education. This consequently has adverse implications in forcing the population to be dependent on some form of handouts.

But the politics and challenges of funding to provide crucial services as well the implications of a lack of prospect for growth and development for the refugees create an environment that is quite challenging to solve.

When I met Mr. Emmanuel Nyabera, the attaché of UNHCR in Nairobi in 2009, he described to me the challenges of operations in an environment where the responsibilities and requirements of the agency had increased thanks to a tense situation in Somalia as well as a massively overpopulated Refugee camp in Dadaab. Yet, the global financial crisis saw cuts in the tune of 24% as governments were scrambling to clean up their house and offer their own systems support.

Massive resettlements of refugees from Dadaab to Kakuma had taken place and today, Somalis make up for the majority of the population, despite the fact that the camp was originally meant for refugees from Sudan.

Funds for the maintenance of settlements have always been difficult to sell to governments and during hard times, a disproportionately large percentage of of the budget for non-emergency operations are cut relative to those for emergency operations. While this makes obvious sense, it goes to show that refugee camps such as Kakuma bear the burden of such cuts. and are thus subject to several variables of political and financial pressures that adversely affect the lives of people within them.

While I haven't drawn focus to the overbearing plight of refugees or even discussed the psycological implications of being so far from home or living as hostage in another land, I do believe that readers should take the time to educate themselves in this domain. There are a number of resources available both from UNHCR as well as platforms setup by refugees themselves such as Kanere.org in kakuma.

Finally about to board the plane but not completely trustful of the situation until we were well inside and seated

UN Town - A convoy of UN cars outside the Ethiopian restaurant, popular among aid workers

Education in the camps

Education facilities fall short of national standards, despite the attempts and focus of UNHCR and LWF (Lutheran World Federation) to prioritize education as one of their most essential services. My own observations were that classes were quite dark and though I only met some students that were attending remidial classes on Saturdays, I was informed by various sources that the classes were also quite over crowded. Teaching quality likewise has a great deal left to be desired.

The resulting implication is that the experience of education is a lot more challenging for refugees and it is praiseworthy to see people graduating from high school and seeking further education despite such impediments.

When we met Mr. Joseph Mutuamba who is in charge of LWF's (Lutheran World Federation) operation of providing education in the camps, he informed us that the issue of girls dropping out was particularly challenging and something that needed to be given a lot more attention. The program that 60 Million Girls had funded was a crucial fix as remedial classes helped these girls keep up as well as provided them with resources such as text books and other support material that LWF cannot provide for in ubiquity.

Girls typically matched the number of boys in a one to one ratio in grade 1 but as the years progressed the dropout rate rose to unprecidented levels. In 2011, we were told, there were a total of 11 girls that sat the final secondary school exams out of which only 3 had passed. For a camp with a population of over 100,000 - this is an alarming statistic. Many of these girls, thankfully, are able to find funding to help them pursue further education in Nairobi or even Canada. To many families, this is seen as a silver lining that has the potential to free them from their poverty striken situation and a consequence of this is an overarching value for education in the camps as a whole. Still, actually pulling through these challenges remain a complex and arduous endeavor.

Joseph stated that one of the challenges is the fact that many of these girls leave and don't come back and there is usually a lack of role models within the system. He laments that teaching is not seen a possible career choice and leaves questions on addressing the quality of teaching as well as guidance for many of the girls.

Indeed, Kakuma requires huge investments in education infrastructure and my recent communiques with people from the camp suggest that education is being given the precendence it requires.

Portraits of Girls

We set out to photograph the beneficiaries of the project initiated by Windle Trust Kenya with financial support from 60 Million Girls. The rest of this section is focused on them.

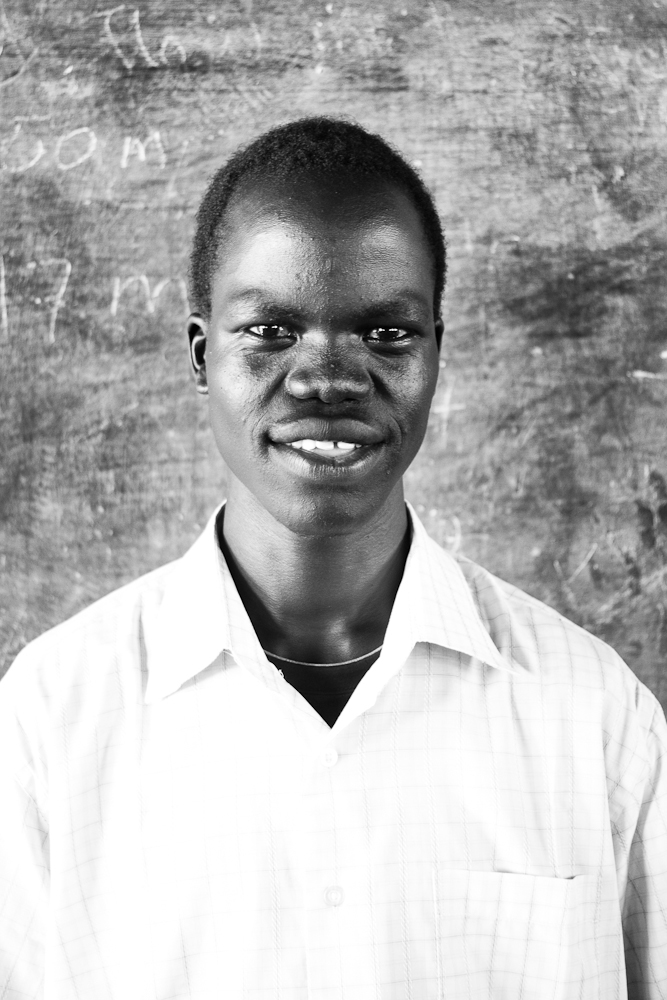

I met Hellen Ayol in Kaduguli Primary School and found her to be quite cheerful. I can't quite decide which of the two photos that I like more but both of them show a certain depth that I find quite captivating. Above, her look is almost melancholic and below, she exudes such a deep expression of happiness that many people have highlighted as their favourite image in the entire set.

A hole in the wall of Horseed Primary, one of the typical cases that represents the lack of adequate infrastructure for education in the camps. This was a saturday but typically, you would find these classrooms rather packed and far beyond capacity. As a photographer, I was also challenged with the poor lighting that was particularly a problem in Bhar-el-naam. Kakuma had recently received a large amount of money from from both the Queen of Qatar as well as UK government. One would hope that these problems would be solved and infrastructural obstacles taken care of.

Amo Sentino is 15 years old and tells me that her favourite subject is Mathematics. She is one of the few girls that will finish their primary education before 18. Many families in Kakuma are quite large with hers consisting of six siblings in total.

Kama Osman, 17 looks away as one of her classmates walks out with a curious look. Kama said she particularly like English and will be finishing her Primary school in the coming year.

Bishar Mwinyi Hamisi was a delight to meet and photograph. In my brief interaction with her, I could tell her virtuousness and general comfort with meeting a perfect stranger. She is only 12 years old - significantly younger than many of her classmates, one of the few that have had an uninterrupted education. My wish for everyone in Kakuma is to see more of these scenarios in the hopes that they will create a better life for everyone as the prevailing norms change.

Isra Yahye had a very honest smile about her. She is 14 years old and says she loves Science.

LEYLA AHMED IBRAHIM

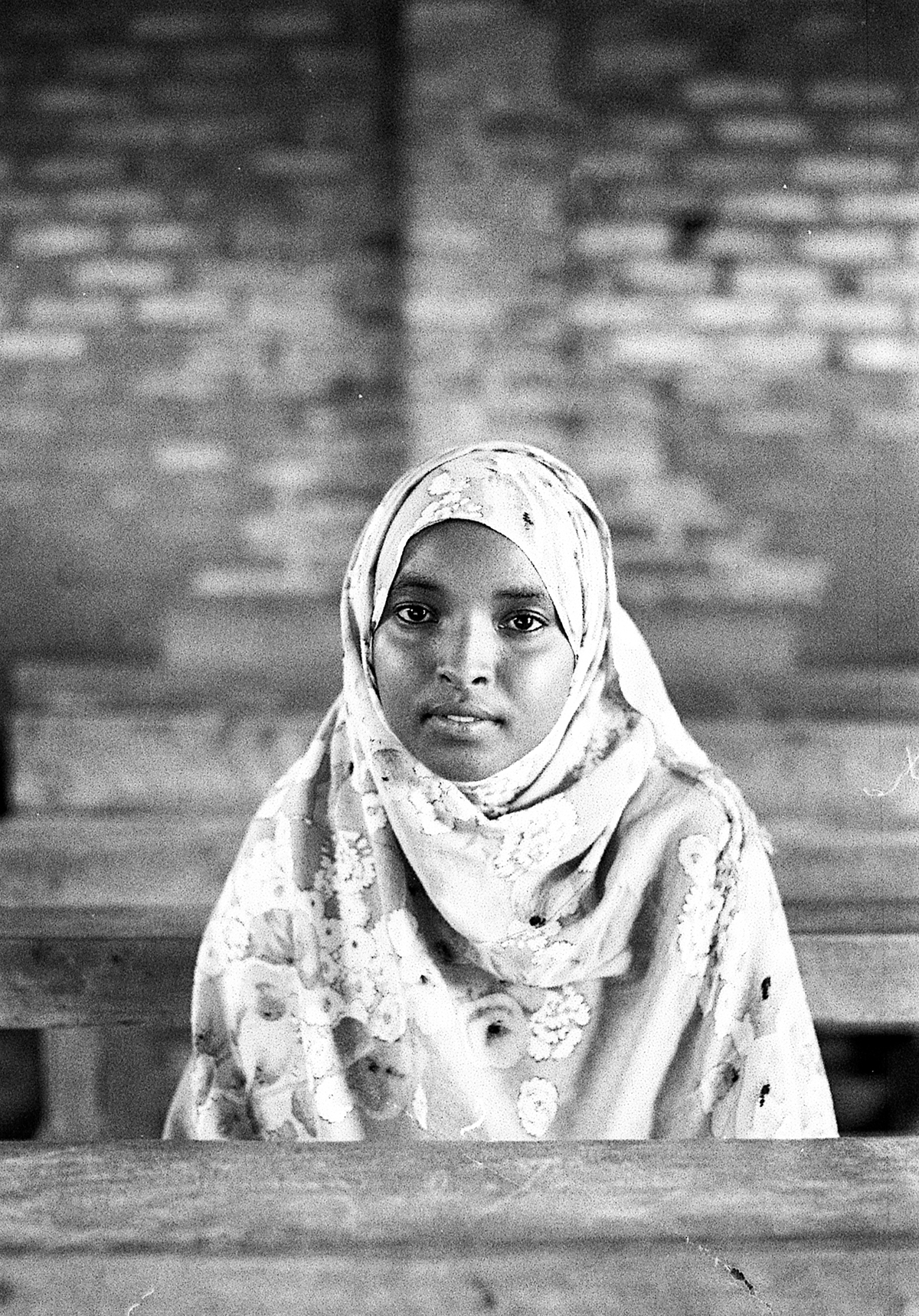

I first met Leyla during the portrait shoot. My first impression of her was not that she was particularly shy in front of the camera but rather that she was quiet and contempt with herself. She had an air that commanded respect and a peacefulness that is difficult to describe.

It is difficult to make conversation in such a set up since you have the task of bringing out artistic portraits but in addition to this, we need to somehow bring to life the stories and go through somewhat of an investigative process. This was my first shoot of this scale and although I had dreamed of doing work of the sort many times, there were several unknowns to factor. Perhaps the hardest part of any shoot that rests on time constraints is to allow people to trust you to a point where you can really capture their personality in the image. They must be themselves and I am well aware that as a photographer, one is quite gifted to feel accepted and trusted.

We spoke for a short period of time, where she told me that she loved science and really enjoyed school and the environment around her.

Thankfully though, I got an opportunity to meet Leyla once again – at her home and together with her family. The setting was very modest but beautiful. They had a veranda where her little brothers, quite shy, played together with big smiles. We were received by her mother with exceptional warmth.

Leyla started to tell us about her life. Her mother had left Mogadishu about 3 years prior and made their way to Dadaab. The camp was full – so they were asked to find their way to Kakuma. I asked her if her father had come with her.

“He is still Mogadishu,” she said and paused for a moment before saying, “with another woman.”

There was an air of unhappiness in her voice that signalled the presence of a story. What story? I didn't feel comfortable delving deeper into this. Yet what I understood was the deep love and affection for her mother. We understood from their relationship that she was her mother's emotional support and one could tell that Leyla in return depended on her mother for her wisdom, experience and support as well. They struggled a fair deal to push their lives forward. It was a bizarre state of affairs in Kakuma as this was the life of so many – such a careful balance of struggle that the risk of falling off has grave consequences.

Leyla’s family were very dependent on the rations provided by the World Food Program and sold some of them to pay for such things as electricity. She paid KSH.1000 (about $13) a month to power 1 bulb and she would receive electricity everyday between the hours of 7PM and 11PM. When you think about it, 1 bulb for $13 a month is quite excessive – a typical case of the poverty premium.

Her typical day was a daily ordeal and show of strength, taking on the burden of being a homemaker as well as pursuing her dream to create opportunity for herself and for those around her.

4 am - wake up and goes to fetch water to prepare breakfast and ready herself and her brother for school

5 am to 7 am - does school work

8 am to 4 pm – Goes to school

5 pm - comes home to do her chores - cleans the house, washes clothes.

5.30 pm - 7.00 pm studies with a classmate as they use the remaining amount of available light and the 4 hours of electricity

7.00 pm - prepares dinner for the house

8.30 pm to - 10.30pm - studies some more

11pm - lights out - electricity only runs from 7 - 11pm Goes to bed.

We asked what she wanted to do in life after she finished her schooling.

“Become President of Somalia,” she said, continuing that all their problems were the result of a lack of leadership and she wanted to make things right.

Leyla has been doing exceptionally well in school and both Manuela and I were taken aback by her resilience. I thought of the amazing relationship she had with her mother and thought of their interdependence for a second. Leyla protected her brothers, offering them love and care and ensuring that they grew up to be men of character. She was her mother’s companion and her mother, having been through a fair bit, was dependent on this friendship for her courage but when she was weak, Leyla would carry the torch forward in what was their family.

A portrait of Leyla's family

VERONICA PANDA

My first impression of Panda was that she was extremely reserved. She kept to herself and was not particularly expressive. I didn't have much in the way of coversation with her.

The next day, we were taken to visit Panda and her family and understand in greater detail what her life was like. Her story is one that resonates among many other refugees – a story where a cloud of insecurity looms large and each day becomes a mere attempt to move on to the next day.

Panda said nothing when we walked in, she was very quiet and we were received by Flora, Panda’s sister. Flora greeted us with a warm smile and her mother rushed to get us something to drink. We were guests at their home, and as is the norm in her culture, she thought we should be made as comfortable as possible. It was incredible because they had very little and depended on food rationings provided by the World Food Program but their show of hospitality was a powerful reminder of the humility among these people. We insisted that it wasn’t necessary and after much of such insistence, she returned and sat next to her son and two daughters. Panda’s mother did not speak English so all our communications were will Flora, who proceeded to tell us their story.

Their mother, Agok, left South Sudan in the early 1990s. Agok’s husband had promised dowry to her family as is custom for marriage – typically a herd of cattle. He was unable to do so, however, and was killed by Agok’s brother. She carried the infant child and walked all the way to the refugee camp to find safety. Here, Flora and Panda were born. Agok’s brother though, was still unmarried as he was unable to make up the dowry to pay for a wedding. His strategy was to get Flora and Panda married off so that the family could have cattle that he could use to find a bride.

He frequently made his way to the refugee camp to convince Agok to give her daughters away to get married. They always resisted but always lived in fear. There is a refugee protection program that they have since signed up for and were hoping to be relocated to the United States – far away from Agok’s brother.

Panda was a very quiet girl. In fact, she never spoke through the entire process of the interview except to say yes or no. Flora was the support in this family just as Leyla was – of strong character and support to everyone. There were deep pressures that are difficult to understand in these situations as one can only dig so deep with the time constraints and agenda present. To me, it was clear that we needed to stay longer to understand the story of Panda. At present, she was a beneficiary of the remedial classes for girls while Flora had dropped out of school.